When An Encounter Takes Place (2025)

![]()

View of the exhibition at Perrotin Tokyo

![]()

View of the exhibition at Perrotin Tokyo

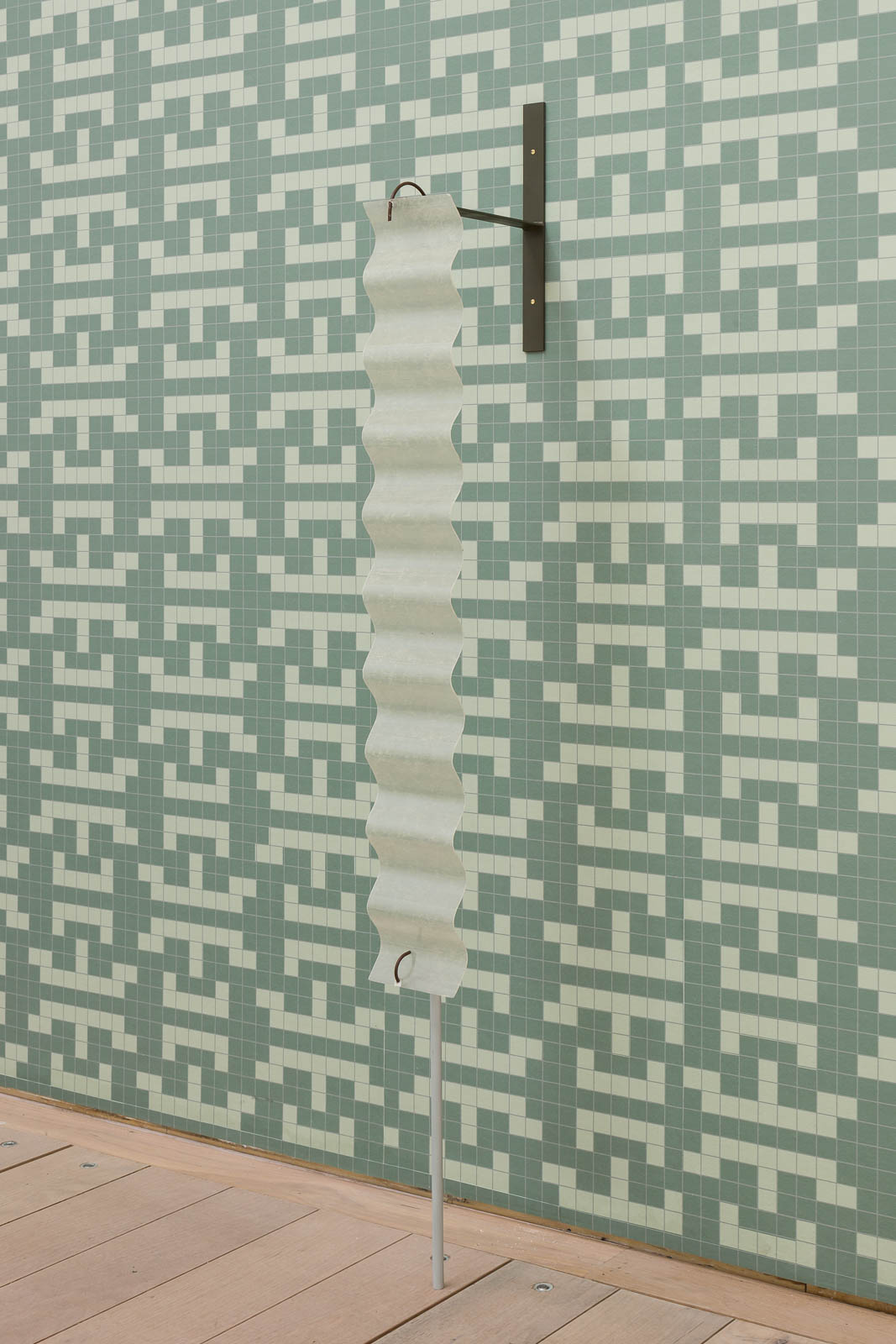

Collision of Fate, 2025, Hand-blown glass, paper, dimensions variable

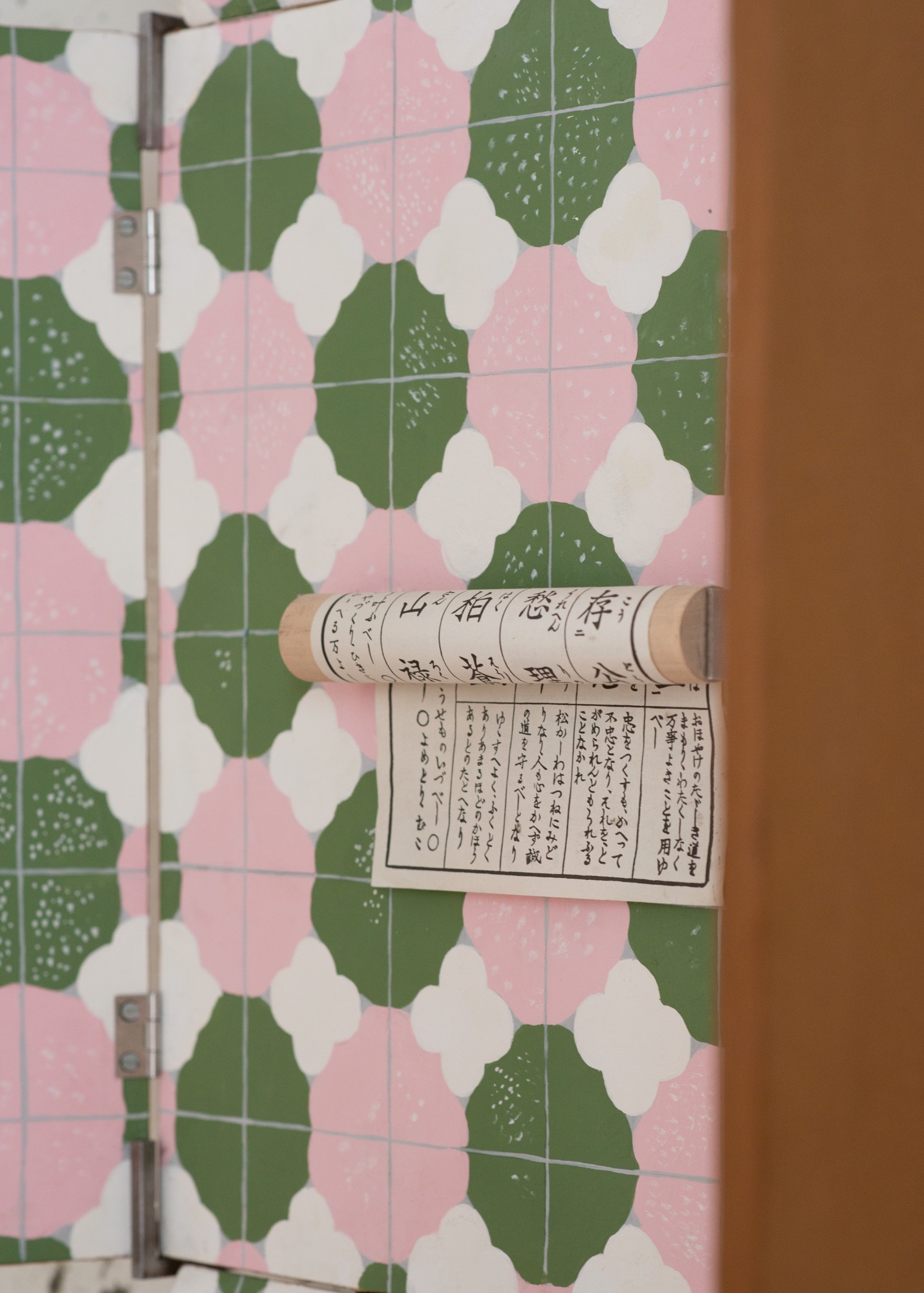

Pachin Pachin, 2025, Wood, dowel, hand-blown glass, aluminium, acrylic, paper, emulsion, stainless ball, 60.7 x 62.8 x 5.8 cm

Resting (detail), 2025, Mild street, hand-blown glass, dowel, nail, 38 x 103 x 8 cm

![]()

Promenade Along the Time (detail), 2023, Glass tube, ladybug, wood, paper, paint, mild steel, stone, emulsion, 47 × 35 × 73.5 cm

Promenade Along the Time (detail), 2023, Glass tube, ladybug, wood, paper, paint, mild steel, stone, emulsion, 47 × 35 × 73.5 cm

Late Night Gas Station, 2025, Hand-blown glass, mild steel, 40 x 25 x 25 cm

![]()

Among the Earth and the Gravel, 2025, Mild steel, printed recycled glass, 75 × 75 × 11 cm

Among the Earth and the Gravel, 2025, Mild steel, printed recycled glass, 75 × 75 × 11 cm

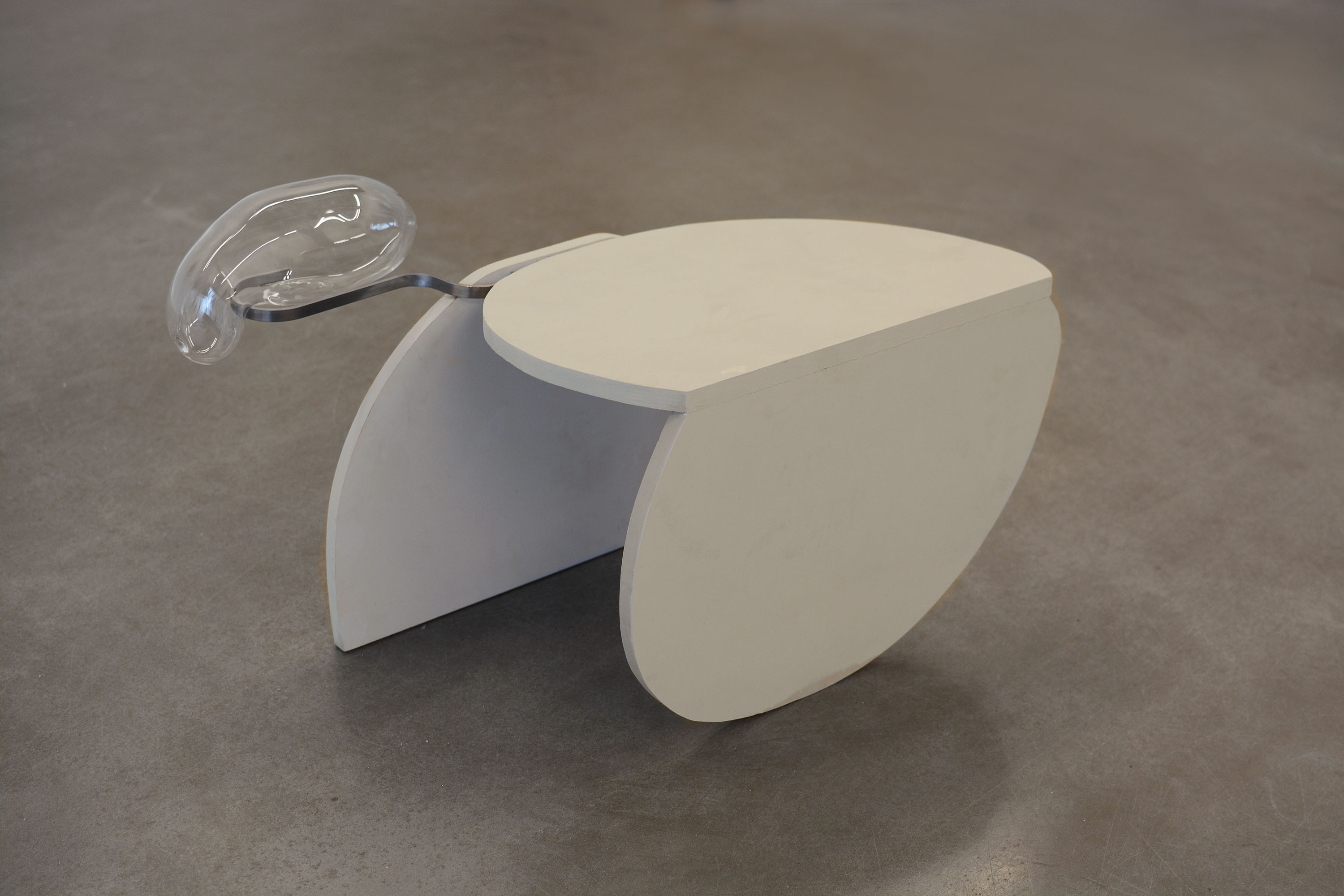

Mediterranean Sea, 2025, Mild steel, hand-blown glass, wood, emulsion, sea urchin, aluminium,

35.5 × 59.8 × 21 cm

35.5 × 59.8 × 21 cm

Momotarō ii, 2025, Hand-blown glass, copper, 25 × 35 × 25 cm

Summit, 2025, Tatami, hand-blown glass, light, Dimensions variable

The Net, 2025, Hand-blown glass, mild steel, 36 x 36 x 14 cm

Momo, 2025, Hand-blown glass, mild steel, 16 x 73 x 39 cm

Le Bleu De L'Eau, 2024 Hand-blown glass, mild steel, bronze, 30 x 42 x 30 cm

Talking Tins, 2025, Hand-blown glass, cooking oil tin, bronze, fishing string, Campari soda, cable, speaker cone, sound, Dimensions variable

Installation view of Talking Tins, C-Lab, Taipei

Late Night Gas Station, 2024, Hand-blown glass, mild steel, 40 x 25 x 25 cm

Cherry Bakewell Sundae, 2024, Hand-blown glass, painted mild steel, mild steel, 60 x 80 x 56cm

Pink Sea, 2025, Hand-blown glass, aluminium, wood, emulsion, 41.5 x 82.5 x 8.5 cm

Earth, Wind, Fire, 2025, Painted mild steel, bronze, concrete, tin, 43 x 52 x 40 cm

Installation view of Lili Deli, Taipei Fine Arts Museum

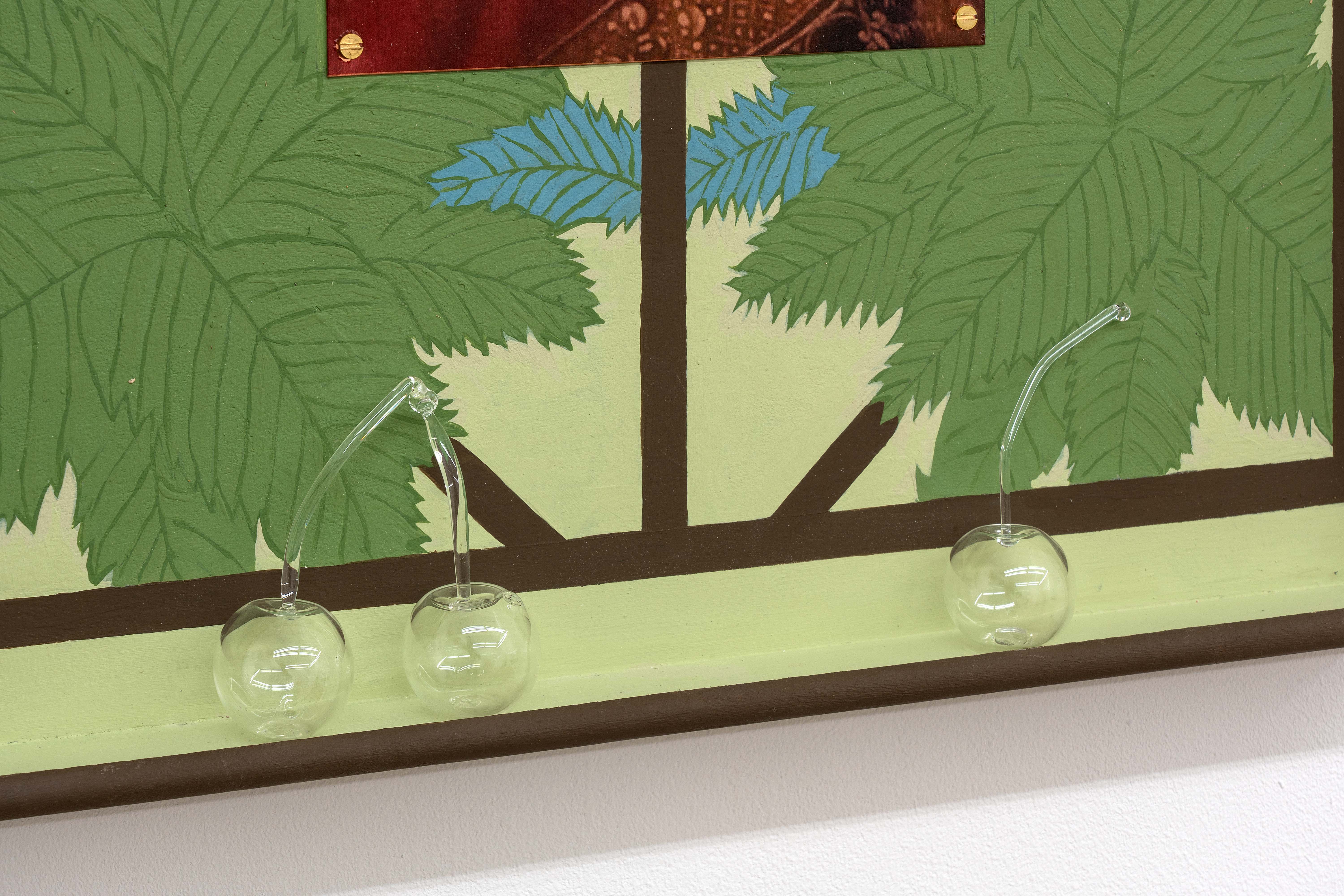

La vie est un bol de cerises, 2025, Hand-blown glass, stained wood

La vie est un bol de cerises, 2025, Hand-blown glass, stained woodProperty for Sale (2024)

Installation view at Hong Foundation, Taipei

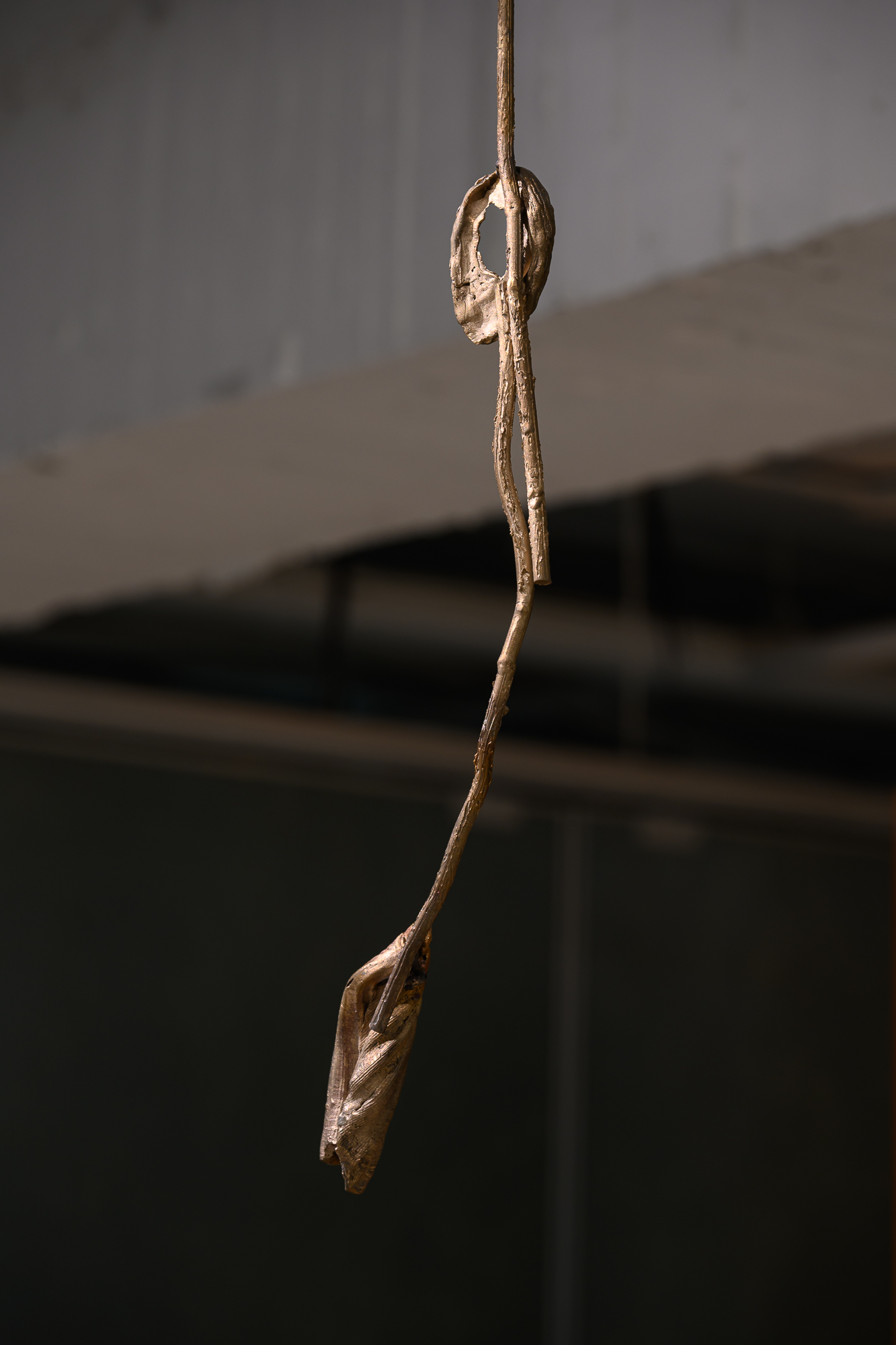

Return Home, 2024, Bronze, 66.5 x 13 x 5 cm

Return Home, 2024, Bronze, 66.5 x 13 x 5 cm

Relocation Celebration, 2024, Plywood, emulsion, hand-blown glass, plastic, glass sand, 74 x 37 x 27 cm

Installation view at Hong Foundation, Taipei

See, See, Sea (2024)

Still image from the film See, See, Sea (2024), Tate Britain, London

Detail of Dolphin Screen, 2024, Stained plywood, glass, copper, bronze, mild steel

Detail of Dolphin Screen, 2024, Stained plywood, glass, copper, bronze, mild steel

Detail of Sunday Shopping List (2024) Found object, bronze

Installation view at Tate Britain, London

There Is Nothing Old Under the Sun (2024)

Installation view at Standpoint, London

“In the end, in every visitation of places, we carry with us this burden of what has already been lived, already been seen, but the effort we are prompted to make every day is that of rediscovering a gaze that erases and forgets habit; not so much to see with different eyes, as due to the necessity getting back our bearings anew in space and time”.

L. Ghirri, Paesaggio Italiano, Milano 1989

The Gone Room, 2024, MDF, wallpaper, 45 x 37 x 2.5 cm.

Art Basel Hong Kong - Discoveries 1C37 (2024)

Installation view at Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre

![]()

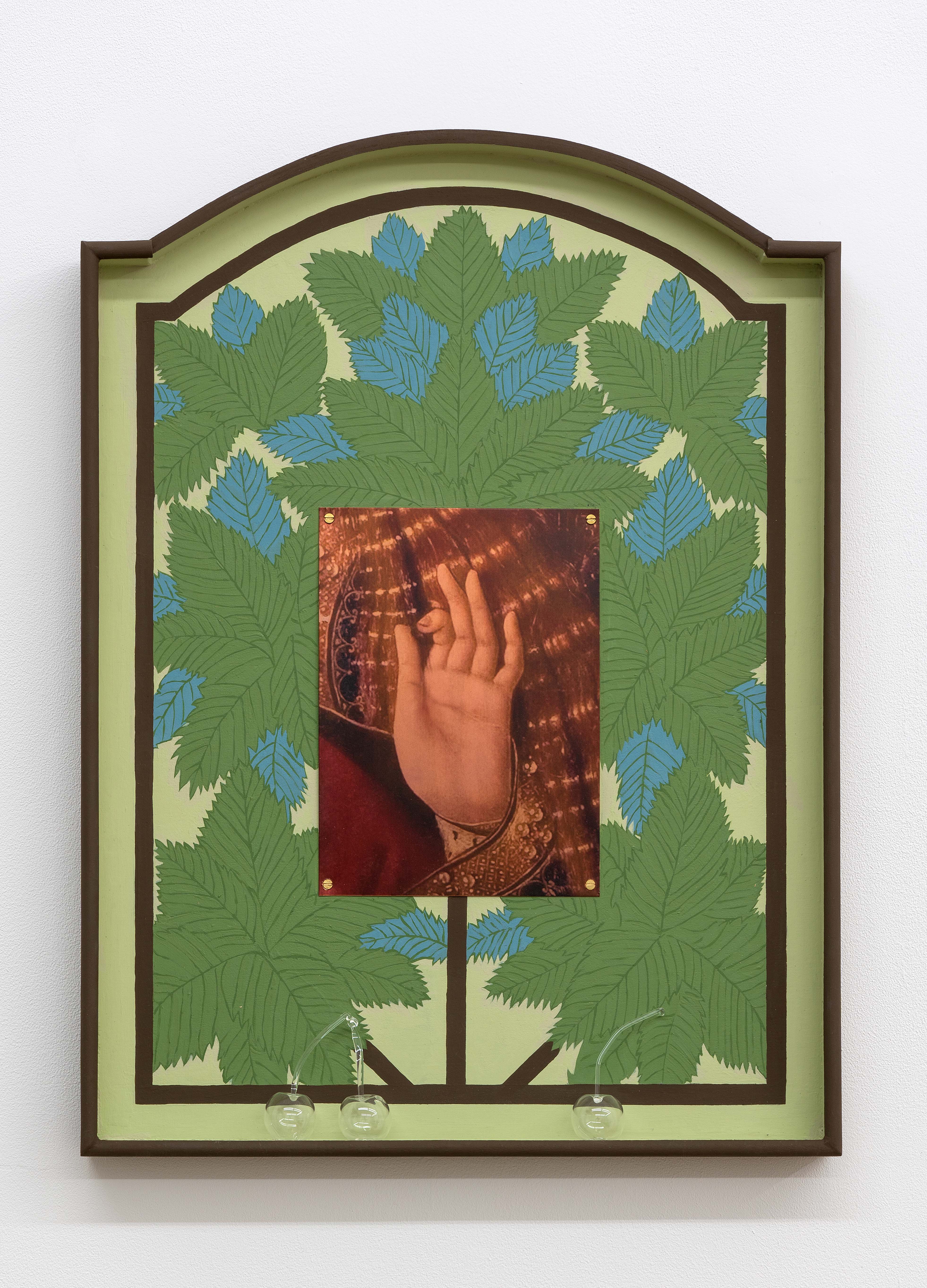

The Liberty Bell, 2024, UV print on aluminum, plywood, MDF, emulsion, bronze,

62 × 38 × 5 cm

The Liberty Bell, 2024, UV print on aluminum, plywood, MDF, emulsion, bronze,

62 × 38 × 5 cm

Quotidian, 2024, Plywood, emulsion, mild steel, hand-blown glass, sapele, 122 × 80 × 60 cm

The Water that Bears the Boat (2024)

Installation view at Gallery 2, E-Werk Freiburg, Germany

The View, 2024, Plywood, paint, aluminium, UV printed recycled glass, light tube, 9,5 x 39 x 29,5 cm

Each Person a Bubble, 2024, Hand-blowed glass, string, speaker, cable, amplifier, sound (00:02:04 min ), 7-piece, site specific

Pillar, 2024, Plaster, copper, paper, hand-blown glass, mild steel, 5-piece, site specific

Installation view at Gallery 1, E-Werk Freiburg, Germany

Installation view at Gallery 1, E-Werk Freiburg, Germany

Pause, 2024, Hand-blown glass, mild steel, 20 x 10 x 20 cm

I Will See You When the Week Ends (2023)

January's solitude, 2023, Plywood, MDF, screen-printed perspex, paint, Christmas tree pine needle, 72.4 x 42 x 36 cm

I Will See You When the Week Ends, 2023, Plywood, hand-blown glass, mild steel tube, bronze, 43 x 140 x 14 cm

Between Sunrises and Sunsets, 2023, UV printed smoked glass, mild steel, tin, 140 × 203.5 × 12.5 cm

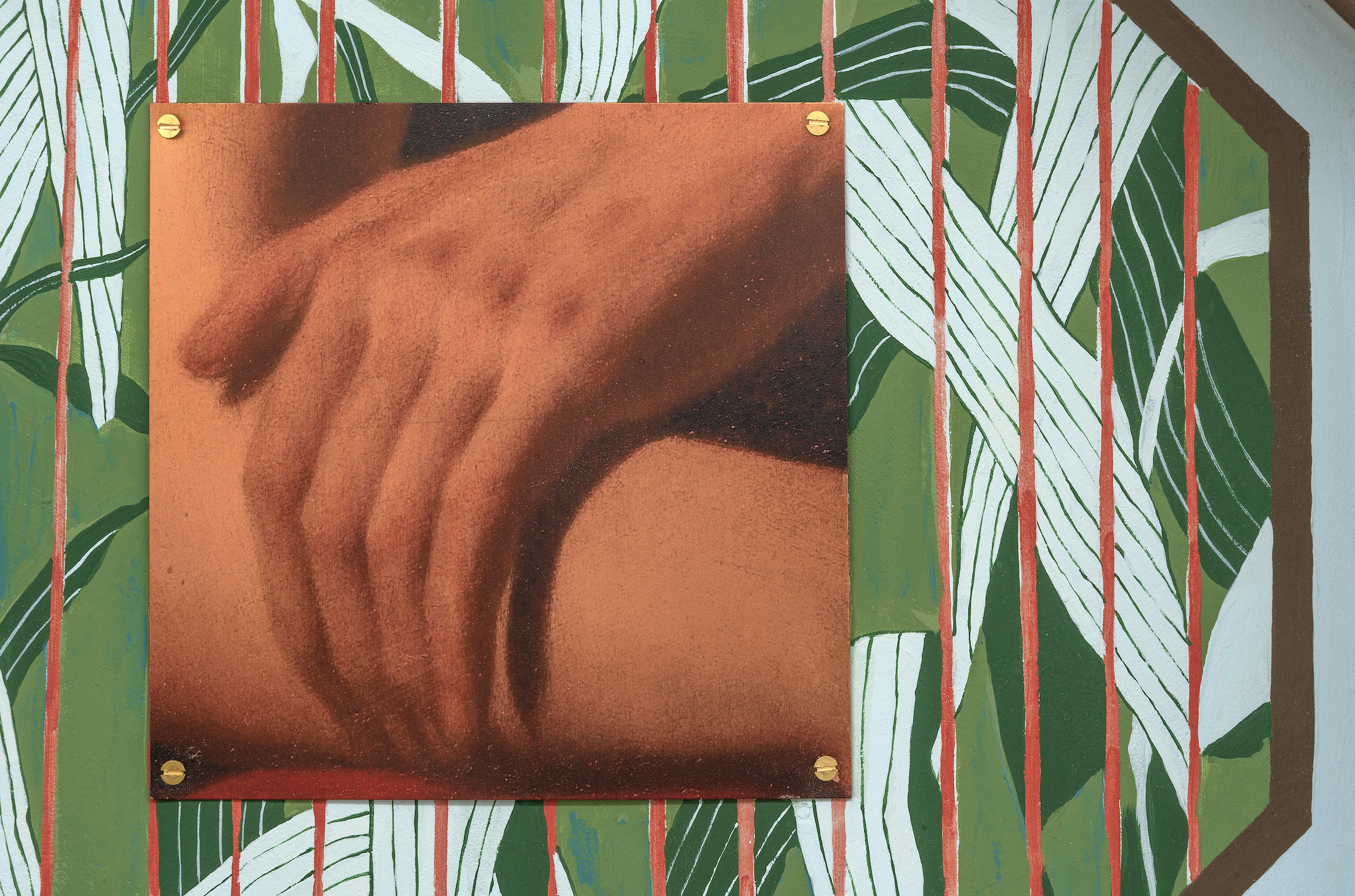

Liaison, 2023, Plywood, MDF, UV printed copper, paint, 41.5 x 41.7 x 7 cm (detail)

Bitterness, 2023, Plywood, MDF, UV printed copper, paint, 41.5 x 41.7 x 7 cm

Out of Order, 2023, Mild steel, tin, UV printed mild steel sheet, paper, 64 x 192.5 x 17 cm

Short-term pleasure, Long-term pain (2023)

Cherry Picker, 2023, Plywood, MDF, paint, printed copper sheet, hand-blown glass, powder-coated mild steel, copper leaf, 55 x 40.5 x 5 cm, 112 x 35.5 x 11cm

Cherry Picker, 2023, Plywood, MDF, paint, printed copper sheet, hand-blown glass, powder-coated mild steel, copper leaf, 55 x 40.5 x 5 cm, 112 x 35.5 x 11cm

(detail)

Prawn Cocktail, 2023, Mild steel, hand-blown glass, 160 x 12 x 14 cm

Deep Shallow (2022)

Installation view at Volt in Eastbourne

Broken Time, 2022, Mild steel, hand-blown glass, sand,

24 x 20 x 12 cm

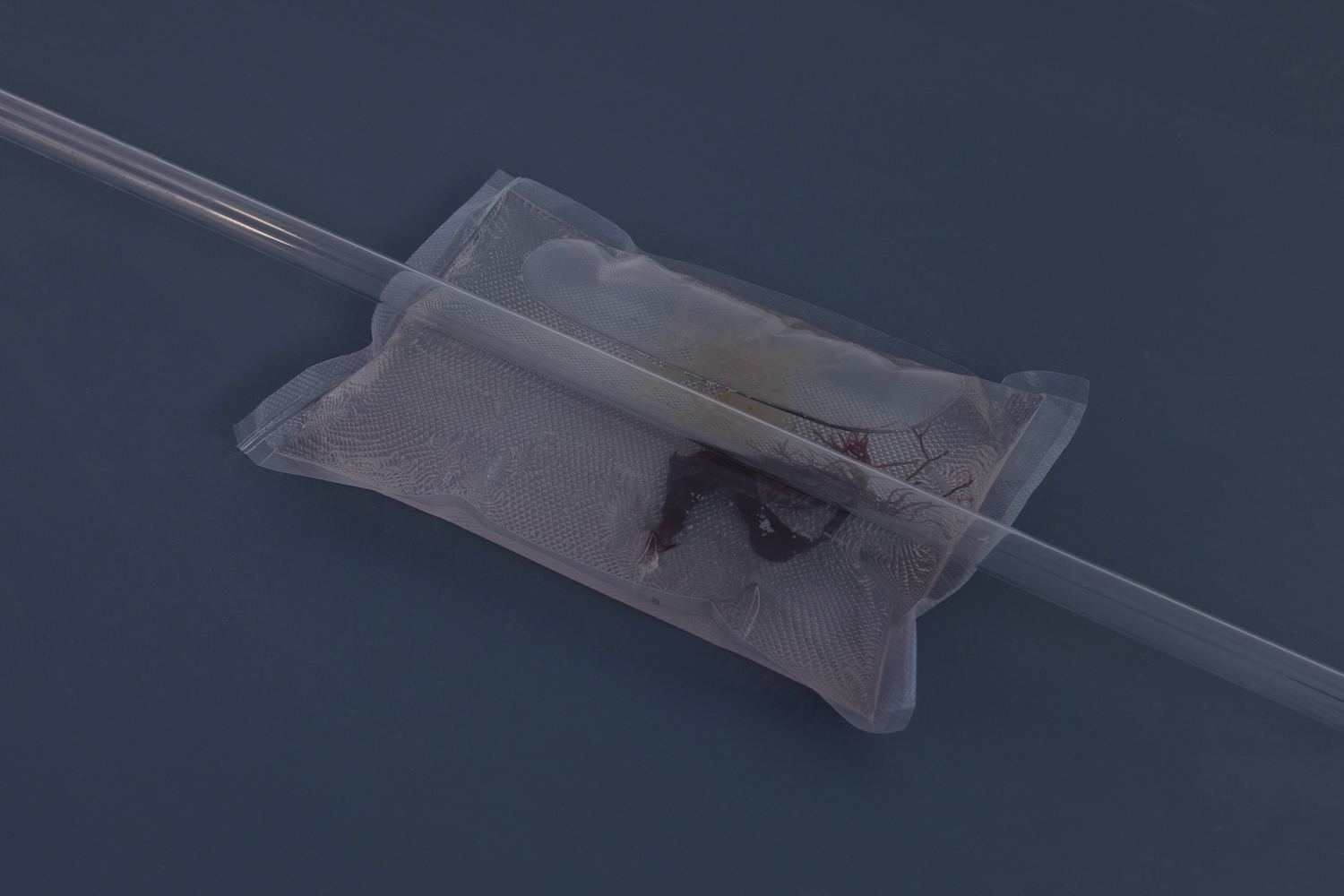

Canoe, 2022, Glass, water, seaweed, vacuum bag,

6 x 155 x 16 cm

This time, I have shifted my focus from food markets to the fishing industry, conducting several research trips to Brixham fishing port, once known as the ‘Mother of Deep-Sea Fisheries. I immersed myself in the culture and communities of the fishing community and was fortunate to work alongside trawlers, basket weavers and lobster pot makers.

Unlike the previous show at Goldsmiths CCA, this exhibition presents a new body of experimental work inspired by the pure blue of Brixham’s seawater and the liveliness of the harbour. Sea-based materials, such as seaweed, fishing ropes and willow, are incorporated into the show, as well as several transparent hand-blown glass floats. This time there are significant proportions of films and sound: the documentary depicts physical labouring and against the nature, which has become less "labour" and more art over time—that refinement and skills of the fishing, fish packing process, and long-hour daily trawling alone with the sound of trawling and crashing waves animate the gallery.

![]()

![]()

Edge, 2022, Plywood, paint, hand-blown glass, powder-coated mild steel, 15 x 90 x 5 cm

Unlike the previous show at Goldsmiths CCA, this exhibition presents a new body of experimental work inspired by the pure blue of Brixham’s seawater and the liveliness of the harbour. Sea-based materials, such as seaweed, fishing ropes and willow, are incorporated into the show, as well as several transparent hand-blown glass floats. This time there are significant proportions of films and sound: the documentary depicts physical labouring and against the nature, which has become less "labour" and more art over time—that refinement and skills of the fishing, fish packing process, and long-hour daily trawling alone with the sound of trawling and crashing waves animate the gallery.

Edge, 2022, Plywood, paint, hand-blown glass, powder-coated mild steel, 15 x 90 x 5 cm

The installation view at Volt, Eastbourne (up) Two-minute film clip - Deep Shallow, 2022 (below)

蒸蒸日上(2022)

Installation view at Taipei Fine Arts Musuem

A Great Increase In Business Is On Its Way (2022)

The primary characteristic that all great markets share – whether they’re in London or Paris, Hong Kong or Bamako – is cacophony. At East Street Market in Walworth, south London, the cacophony is almost like Babel.Of course there’s sound, the sound of a thousand things being sold in Yoruba, Urdu and Cockney, the sound of pleas, haggling, recognition, peals of laughter, the musicality of vendors and the literal music of Kurdish lovesongs and Afrobeats on the radio. But there’s also a cacophony of other senses that are difficult to resolve: thesmell of ripe mango and stockfish and, what is that? Iru? The cacophony of handwritten signs vying forattention, each a different font, each promising a better deal: 5 for 3, 3 for 2, 2 for 1. The cacophony ofrecognisable objects being used for things they were not intended for, upturned blue pallets becoming integralinfrastructure. A man holding aloft an extra-large pair of Y-fronts as he stretches them as far as they can go,while a customer skeptically deliberates. ‘How big are his nuts?’ the vendor laughs.

Cacophony is not a characteristic of all markets. The markets whose sounds, sights and textures are featured inSteph Huang’s exhibition A Great Increase In Business Is On Its Way are markets, the last markets maybe, thatstill serve London’s diverse working-class communities. East Street. Ridley Road. Deptford. These are not themanicured markets that exist to sell tourists hot food, or the street food ‘markets’ which only exist to monetisepseudo-public space – all of which are monophonic, in chorus, harmonious – but markets that catch fire offtheir own friction, pushing people together in spaces that are, as anthropologist Jess Fagin puts it, ‘fraught withthe tangles of being remade and claimed by people who live in the city’.

These markets animate not only the city as it is now, but the historical flow of global trade that in a supermarketmight feel abstract: here you can track the spread of spice to London – cardamom, mace, nutmeg – that may well end up in a Nigerian soup or a Pakistani curry rather than scenting a pudding, while under the counterdealings reflect the absence of official food chains for ingredients the British have not yet taken an interest in. Whereas the supermarket ranks things into a set hierarchy (Taste the Difference, Essentials, Basics) the language of quality at markets is more ambiguous (best, premium, fine, selected) while being subject to the norms andstandards of different cultures, dietary requirements, and superstition. ‘Great knowledge circulates within amarket’ says writer Camilla Bell-Davies. In this sense, the faces of a kola nut, the multiple meanings of a pig(fertility to some, verboten to others, cops to many), the many foods that break the year into its parts, that offer good fortune on certain days, represent the great collective knowledge of the city. The market is history, economics, colonialism, inequality, community, divination, Sunday shopping and dinnerall happening at the same time.

The messiness and absurdity of public food spaces is a theme that runs through Huang’s recent work. Her 2019 exhibition Everything about Prawns looked at Taiwanese prawn-fishing halls where workers escape the drudgeryof labour and the isolation of the home by finding a shared, communal space on industrial estates to fish, cookand eat their own prawns. In 2020’s Four Legs Good, Two Legs Bad, Huang connected the advent of Taiwanese shopping centres to trips along the highway where trucks carrying live pigs might be spotted, in a kind of surrealopen-air installation. When I recently talked to Huang, the topic of the bingo hall on the top floor of theElephant and Castle Shopping Centre quickly came up, a space which has featured in Huang’s art and that the architecture critic Owen Hatherley called one of ‘the most genuinely open and democratic spaces in the wholeof central London, used by people from all walks of life’.

What connects the prawn-fishing halls, the markets, the bingo hall is their ability, in the most unromantic waypossible, to become communal spaces that momentarily level many of the divisions that exist in our cities:between seller and buyer, cook and eater, Black and white working classes, all eating the same Jamaicansubsidised meals amid a Lynchian carpeted landscape. They remind me of the Japanese bar Chris Marker oncedescribed in his film Sans Soleil as ‘the kind of place that allows people to stare at each other with equality; thethreshold below which every man is as good as any other—and knows it’.

I don’t, nor does Huang, wish to represent these spaces as melting pots with smooth consistencies – rather theyare full of tension and contradictions; their primary motivation is not communal or utopian but economic. What stops them from becoming Babel is their ability to produce fusions: a Cockney fruit-seller becoming wellversed in the qualities of papaya, a South Asian street vendor learning the Igbo words for tripe; these are asunexpected as the willow pattern china produced by British factories, or the red-white-blue shopping bagscreated in Japan which have unintentionally become both a symbol of Hong Kong democracy and an integralfashion accessory for every auntie carrying a food haul from the market, no matter what nationality. Huang hasan eye and a love for these details; they may be small, but they are the stuff of life, nonsensical andunpremeditated.

There is one last important feature that all markets share, and that is precarity. There is the everyday sort ofprecarity, a protean quality of shapeshifting where yesterday’s debris is reused and repurposed, where everythingtoday is not quite the same as what it was before, where quality is not assured, where the vendor you love todaymay not be there tomorrow, where everything decays. And I see Huang’s interest in material transformation,turning trotters into candles, sausages into glass, as a way of attempting to make the temporary permanent. Butthere is also an existential type of precarity, one that gnaws at the heart of markets in London as well as furtherafield.If you have a look at the book that accompanies this exhibition, you will find photos of markets that representanother attempt to make the temporary permanent. The market in Leeds’s Kirkgate already announces itsclosure; the eerie, empty halls of Elephant and Castle are already gone, as well as the bingo hall, about to bereplaced with everything you can predict a new London shopping mall might look like. Ridley Road is stillthere, but for how much longer? How long can these places hold out, besieged by the omnipresentfinancialisation of space and time that defines living in London in 2022? How long will the messiness of spacesin the centre be tolerated? How long before they are swept to places out of sight?

The title of this exhibition, A Great Increase In Business Is On Its Way, is taken from a message in a fortune cookie, one of those other incoherent mistakes whereby a Japanese invention becomes adopted by a Chinesecommunity for the delight of Americans. It’s a story of economic survival and co-option, the same as all markets. It is also a statement of fact. London is expanding, getting bigger, getting richer. There is surely a great increase of business on its way, though this exhibition might well make you wonder: for who?

text by Jonathan Nunn

Open Bar (detial), 2022, Plywood, powder-coated mild steel, bronze, glass, fibreglass, paint, Campari, cotton, 102 x 100 x 320 cm

Mortadella Bologna, 2022 Cotton string, hand-blown glass, 25 x 12 x 12 cm

Vagues, 2022, Powder-coated mild steel, fibreglass, 113 x 23 x 10.5 cm

Vagues, 2022, Powder-coated mild steel, fibreglass, 113 x 23 x 10.5 cm

Seascape, 2022, UV print on PVC strip, mild steel, 237 x 75 x 51 cm

Do You Hear the People Speak? 2022, Plywood, speaker, cable, hand-blown glass, dowel, tin, sound (00:06:00), 110 x 18 x 32 cm

Everything and Nothing (2022)

Installation view, Courtesy the artist and mother’s tankstation Dublin | London

Balance of Terror, 2022, Weathered brick, powder coated mild steel, rubber, 60 x 36 x 12 cm

Forest, 2022, Mesh metal, mild steel, bamboo leaves, 108 x 73 x 28.5 cm

Forest, 2022, Mesh metal, mild steel, bamboo leaves, 108 x 73 x 28.5 cm Enjoy Your Meal, 2021, Baguette, hand-blown glass, powder coated mild steel, string, wax, 81.5 x 98 x 5.5 cm

Enjoy Your Meal, 2021, Baguette, hand-blown glass, powder coated mild steel, string, wax, 81.5 x 98 x 5.5 cm Tea Ceremony, 2022, Plywood, mild steel, hand-blown glass, paint, 28 x 44 x 27 cm

Tea Ceremony, 2022, Plywood, mild steel, hand-blown glass, paint, 28 x 44 x 27 cmFragment/abandonment/drifting/intuition/oscillation/transience/alienation/passage/caesura/solitude

It’s a very grey January day… [fragment]… typing that in, my old iMac, (too-passed-it to any longer be of any use to anyone in the gallery office [abandonment], and hence, now mine, and now, situated before a window, looking out onto said grey day at our home in the Irish countryside) suggests, rather prompts, that it is January 22nd – it’s actually the fifteenth. But what’s a week here and there, particularly these days? The computer also took about twenty-five minutes to start up, so it’s little wonder that clock and calendar are a tad out [drifting]. I wonder what year it thinks it is? Let me, however, not get your imagination too carried away with itself, running loose and free, as I would place a small wager that you are visualising one of those really vintage-type Macs, the ones with the transparent cone-shaped teal casings, perhaps, even the tiny-screened, cream plastic ones that went a nasty yellow, after a time, in the sunlight, and had the keyboard that almost broke the sound barrier, [[[ klonk, klonk, Klonk, ]]] as you hit (literally) the keys. It’s not that bad. Though in a retro way, it might actually quite suit the room. I like this room, spend a lot of time in in, write in, I do (says mts ghost writer in Yoda-like sentence-structure, syntax… yes we watched it over Christmas). It’s got a lot of art in it – the room, not Christmas or Yoda; twenty-eight, maybe nine, at a quick scan. At the beginning of the first lockdown (when was that – I better ask my computer [!], we eventually got around to installing a chunk of the gallery’s collection, that had been sitting about the place, just resting, for quite a long time, actually. Two of the more recent additions, a buff-over-painted wire rack attached to the wall, which looks like it originated as a refrigerator bottle rack, and now vertically-aligned hosts a hand-blown glass ‘bubble’, like a tumour bulging around its rigidities. Just below it, on a small modernist tripod table shaped like a kidney, sits a slightly disturbing, pink wax cast of an amputated pig’s trotter. Art can be surprising/should be surprising. 1 Again, it’s vertical and beside an internally illuminated globe of the world that used to live in Finola Jones’ (bossperson) family living room as a child. The globe is permanently orientated to show Australasia and Southeast Asia. A part of the world that means a lot to us – where we met, loved, lived and still feel culturally connected to. There is also a Eucalyptus tree – planted for much the same reasoning – directly out my window, now higher than the house (needs cutting back)… A day later, (the 23rd/16th) the same scene has almost spring-like sunlight upon it. Light (Lee Kit-like) dapples on the wall through the Eucalyptus foliage.

You may by this point, start, legitimately, to wonder what this has to do with Steph Huang [intuition], a young-now-London-based-artist, but most recently of the Taiwan parish. The answer is pretty simple, everything and nothing. In that anythinghas absolutely everything to do with nothing, that in turn, has nothing to do with everything. In a text, ‘FRAGMENT(s’, that has significantly influenced Huang’s present thinking, by the painter and writer Jonathan Miles; he notes; “Il y a (there is) is a term employed by both Levinas and Blanchot, which is a double figure [oscillation] of not anything but neither being nothing, implying that everything has been withdrawn. It relates to a state that is interminable, like insomnia, in which the arrival of the day appears impossible. It has a quality of a presence that lurks [much like my computer’s clock and calendar], or is like an incessant murmur, that solicits the feeling of horror in which the subject is stripped of subjectivity. The relationship between literature and philosophy is mediated by “il y a” which affirms simultaneously the presence of being and the presence of the absence of being, thus refusing incorporation within the totality of history or time. The “il y a” precedes the concept as its simultaneous condition of both possibility and impossibility. (see footnote No.4) ”Nothing comes from nothing.” 2

Steph Huang is also the artist responsible for both the wire rack and glass sculpture 3 and the waxy pig’s trotter. When we visited her in the tiny but absolutely immaculately organised workspace at the Studio Voltaire complex in South London (masked and as socially distanced as the tiny footprint could allow – even all of that, from this morning, is about to be history, the past, passed [transience]), from where she is currently making a new show for mother’s tankstation in Bethnal Green, she handed over a sheath of notes 4, in reference to Clarice Lispector [alienation], Simone Weil and Walter Benjamin, and a list of ten, relatively random words, that were on her mind as she had been cutting and bending things. Huang, I suspect somewhat self-deprecatingly, has expressed; “I mainly think through making”. 5

The next thing (oddly nearly nothing) that caught my attention was the meticulous organisation of space and the present absence of the tools of Huang’s trade. Files (the raspy sort), saws, clamps and blades etc, were all stored away in racks and carefully ‘categorised’ in order of ascending and descending scale. Given the exploration of ‘ideas’, similarly ordered into a kind-of-neatly-amenable randomness in FRAGMENT(s, and the arrangement of the studio (the ‘putting away of’), it was evident that we were engaging with a proprietor of very particular, practical perhaps, but specific interrogative intelligence. A bibliographic sensibility perchance: wherein the process of making has equivalences to managing literary materials by identifying and recording ‘data’ for each item – shapes, colours, textures, materialities, and organising it for retrieval (by others) in a manner desired by (desirous of) the maker/thinker. If indeed Steph Huang does think through making, it is a thought process organised as data retrieval into a sort-of non-linear taxonomy – the organisation and categorisation of things – collated into sensory narratives, [de]posited in stratified layers, accumulating as a historical process, of not anything, but neither being nothing.

Possibly and impossibly, I wonder if the orbit around the ideas of ‘everything and nothing’ is even partially, tangentially, abstrusely, influenced by the dialectical political relationships of Taiwan (ROC – Republic of China) to both Japan and the PRC (People’s Republic of China), as well as the tangential connections of anything to everything, which evolves in the storytelling accretions of Huang’s sculptures and installations. Steph’s work clearly amasses from her experience of Taiwanese cultural paradigms; culture culture and living cultures, food, apartment layouts, decoration, homewares, family, generationality, and the exploration of how one finds a new way of life, away from them, it, newly alone and literally, without. [passage] The sound of a metronome emanating from the handmade doppelgänger of a room-dividing screen, it beats the time of Huang’s absent piano.

A little history: Japan’s colonisation of Taiwan commenced in 1895, and throughout the twentieth century, Imperial Japan continued a slow expansion until the 1930s, when military leadership took the reins of power in Tokyo and began to aggressively expand throughout Asia. The power-drive for empire, as well as Tokyo’s official control of Taiwan ended in ignominious defeat and infamous mushroom clouds of death, in 1945. Subsequently, with the signing of the San Francisco Treaty in 1951 and the improbably named Treaty of Peace, between Japan and China in 1952, Japan officially ceded all claims to Taiwan. But left a legacy of cultural love/hate. Upon attaining independence from the American occupation in 1952, the Japanese leadership followed the United States, and much of western powerbase, in maintaining official diplomatic relations with the Republic of China or Taiwan, rather than the People’s Republic of China in Beijing. However, Japanese leadership tacitly understood that, for the efficacy of post-war recovery, trade with Mainland China (PRC) would be indispensable. Thus, an ambivalent China policy that inclined Tokyo toward a de facto “Two Chinas” policy emerged, a state of neither this, nor that, a double figure of Il y a. But history is just a story (?)

One of the joys of writing, [caesura] is that if you apply enough words to proverbial paper, almost everything, every argument, turns towards ‘nothing’, as elegantly exemplified in Danto’s Analytical Philosophy of History. 6 Danto argues that to ask the significance of something is to ask a question which can only be answered in the context of a narrative story – that presupposes, or is predicated on, a complete philosophical history of past, present and future. A complete, therefore, impossible understanding of everything, as the future cannot be known, hence the double figure, everything is nothing. In short, the nearest we get to understanding, is storytelling, which in it-self is determined as a matter of scope – stories only work if you leave things out – wherein increasingly complex middles are required to explain the outermost edges. Beginnings and ends, which pretty much encapsulates Huang’s work. Danto “represents this graphically as follows” 7, (arranged like Steph’s tools):

()

(( ))

((( )))

(((( ))))

…((((( )))))…

Reconstruct the same data differently and the outcome is quite something other:

((( )))

((((( )))))

(((((((( ))))))))

(((((( ))))))

((( )))

(( ))

(( ))

__________((( )))__________

[solitude]

(( ))

((( )))

(((( ))))

…((((( )))))…

Reconstruct the same data differently and the outcome is quite something other:

((( )))

((((( )))))

(((((((( ))))))))

(((((( ))))))

((( )))

(( ))

(( ))

__________((( )))__________

[solitude]

1 Further examples; include an electrocuted stick and a pair of maracas wrapped in starlight-patterned socks (both Nina Canell). A dysfunctioned laptop hard drive, with a thumb drive (functioning) implanted in it, literally in the form of an amputated thumb, Yuri Pattison. And right above me to my left, a pair of aluminum casts, one above the other, of Styrofoam packing (heavy) that forms a kind of robot face, Brendan Earley. A transistor radio, over-painted with a ‘Dixie’ flag in monochrome black and white, Garrett Phelan. A handsome handwritten letter in copperplate blue ink, in French, and purporting to be date from “20 janvier, 1861”, Dahn Vō. A hand-painted ceramic tile of a topless man, well wearing a hat, smoking a pipe, Noel McKenna. A small painting of a rabbit holding a fluorescent pink skull wearing aviator sunglasses. Atsushi Kaga. You see what I mean?

2 Nothing comes from nothing (Latin: ex nihilo nihil fit) is a philosophical dictum first argued by Parmenides, that appeared in Aristotle’s Physics: It is associated with ancient Greek cosmology, such as presented, not just in the works of Homer and Hesiod, but also in virtually every internal philosophical system: there is no break in-between a world that did not exist and one that did, since it could not be created ex nihilo in the first place. The Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius also beautifully expressed the principle in his first book of De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things):

But by observing Nature and her laws. And this will lay

The warp out for us—her first principle: that nothing’s brought

Forth by any supernatural power out of naught.

For certainly all men are in the clutches of a dread—

Beholding many things take place in heaven overhead

Or here on earth whose causes they can’t fathom, they assign

The explanation for these happenings to powers divine.

Nothing can be made from nothing—once we see that’s so,

Already we are on the way to what we want to know

– The idea is also somewhat perverted in Joris-Karl Huysmans (1884) Against Nature (À Rebours), a novel about the rich but jaded aristocrat Des Esseintes, and the isolated life he crafts for himself – a life governed by aesthetic considerations and the desire to subvert, and even supersede, nature. Nothing good comes from it. Lear also responds to Cordelia’s guttural utterance of “Nothing”, in Act 1, scene 1 of King Lear: “How? Nothing will come of nothing. Speak again”.

3 Exhibited in her MA graduate exhibition, Royal College of Art, London, 2021

Aqua Viva, Simone Weil, Notebooks (Vols. 1&2) and Walter Benjamin’s, One Way Street. “The reader is simply invited to wander (and wonder) within this labyrinth-like organisation of fragmentary texts. There is of course a whole array of preoccupations that are woven into these dis-continuous encounters…” the notes begin…

The brief chapter-like passages are; The Fragment, Out of Tune, Mysterious Guest, Unrepresentable, Pollen, No-place, Strange, Ladder, Pause, Leaden, Disruption, Curved, Abandonment, Affect, Steps, Drifting, Inscription, Obscure World, etc., Withdrawal, Semiotic, Presentation, Maps, The Call, Double Eyes, Marginal, Factory, Violence, Original Experience, Deceased, Il y a, etc.

5 Extrapolated from an email conversation with the artist.

6 Arthur C. Danto, Analytical Philosophy of History, Cambridge University Press, 1964. Along with Winnie the Pooh, my favourite book.

7 ibid., pg.241

text by David Godbold

Verbalise Vase, 2022, Mesh metal, speaker, cable, amplifier, sound (00:02:00), hand-blown glass, 79 x 64 x 29 cm

Non-Functional, 2022

Plywood, mild steel, paint, hand-blown glass

45 x 65 x 22 cm

Inedible, 2022

Plywood, mild steel, paint, clay, pigment

45 x 65 x 22 cm

Out of Tune, 2022

Plywood, mild steel, paint, metronome

45 x 65 x 22 cm

Escape from Where We Are (2021)

Aluminium, chrome plated steel, flour, found object, glass, Japanese paper, leaf, paint, perspex, plaster, plastic, plywood, powder coated mild steel, string, wax

Dimensions variable

![]()

Aluminium, chrome plated steel, flour, found object, glass, Japanese paper, leaf, paint, perspex, plaster, plastic, plywood, powder coated mild steel, string, wax

Dimensions variable

The installation Escape from Where We Are is my response to the experiences of staying at home and traveling during the pandemic restrictions between London, Paris and Taiwan, reusing, refiguring and dismantling found materials and objects. I collected most of the materials from streets in Paris and the abandoned childhood home I lived in again briefly during my quarantine in Taiwan.

The installation Escape from Where We Are is my response to the experiences of staying at home and traveling during the pandemic restrictions between London, Paris and Taiwan, reusing, refiguring and dismantling found materials and objects. I collected most of the materials from streets in Paris and the abandoned childhood home I lived in again briefly during my quarantine in Taiwan.

[Detail] Glass, plaster, powder coated stainless steel

Future Message (2021)

Aluminium, Japanese paper, mild steel, paint, plywood

73 x 50 x 22 cm

‘Future message’ on hinged panels in the shape of a French First

Aid sign examining our need for superstitious beliefs and certain

collective behaviours in times of stress. In Taiwan people often

visit the temple to get a ‘future message’. By putting a coin in a

slot you receive a number referring to your message like an

automated fortune teller, easing the believers’ anxiety and stress.

Three red ‘Pig Coins’ made in Perspex are wedged between wire shelves from a fridge I found in Paris. These “Pig Coins” are similar to tokens used in casinos and might be connected to buying some kind of future message or even crypto-currency.

Sundance (2021)

Chrome plated steel, found object, glass, leaf, paint, plaster, powder coated stainless steel

40 x 40 x 160 cm

Reflecting my belief in the potential of objects to heal, the glass snake in the sculpture entwined around a palm tree made from objects collected from my home, refers to the ancient Greek symbol for health and medicine. A plant pot filled with recycled glass sand stands on a column made of green plaster Canelés (French pastries). I also included other found objects and leaves from tropical plants that for me represent the exotic and the history of colonialism.

A baguette and a glass sausage are from the nostalgic memory of a normal day spent at a cafe and walking on the streets in France. Underneath the baguette, there is a Hungarian text on a block of wax butter saying: Enjoy your meal!

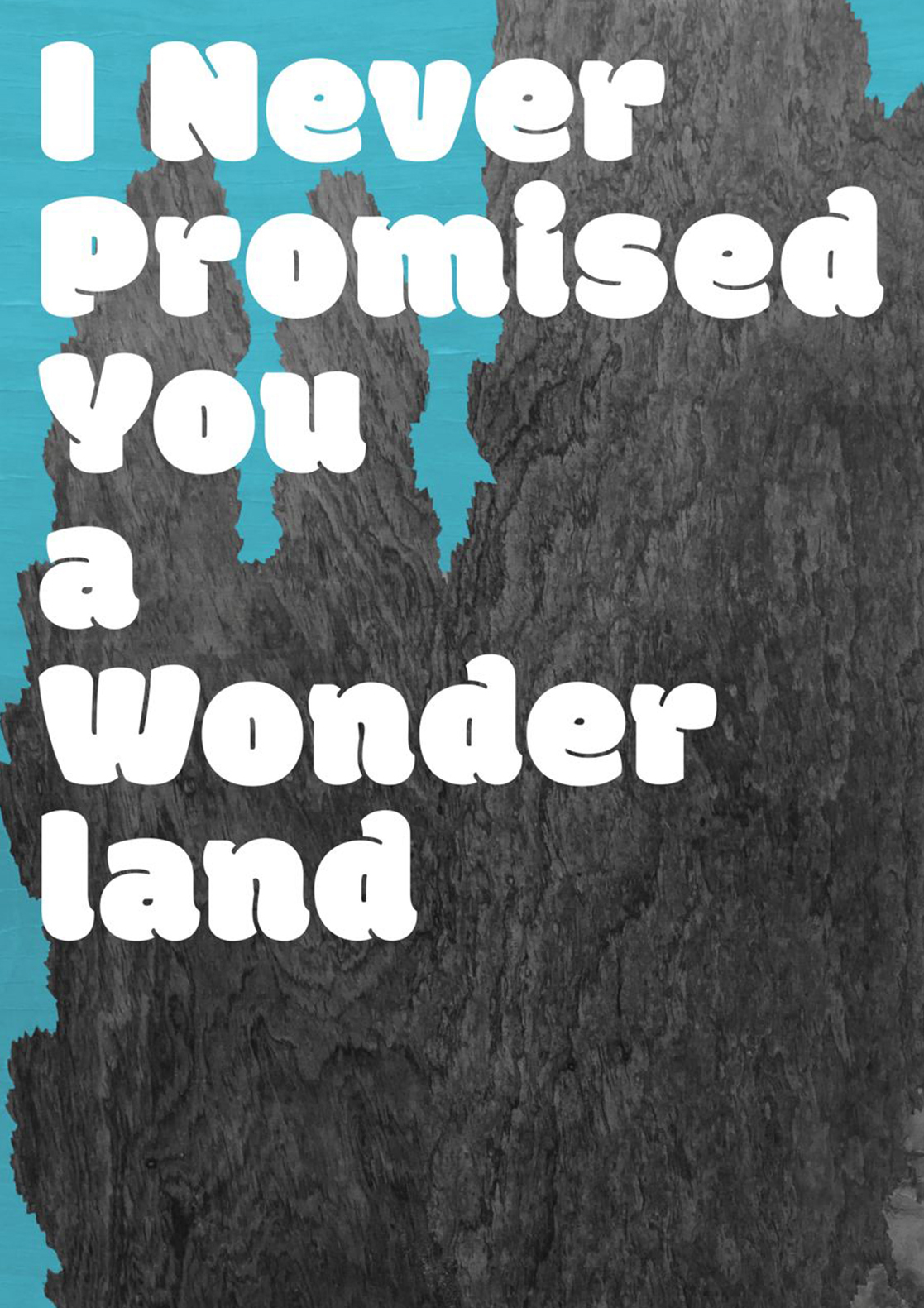

I Never Promised You a Wonderland (2020)

Installation view @Barbican Art Trust Group

It is a new set of works made in response to a 6-week residency at The Barbican Arts Group Trust.

During the residency, I explored the absurdity of life and the fragility of human beings through looking at certain belief systems seen as universal across all cultures of mankind. Setting aside religion, there are numerous ordinary objects designated to offer us false hopes and reassurances. The blind belief we tend to have in objects such as Bonsais, mineral stones, horseshoes, four-leaf clovers, or rabbit feet have created expectancy in our subconscious mind and keep us weathering through the unknown future. Worshiping such deified objects evokes profound emotional responses and further changes our neural functioning. I chose certain symbols that represent just such responses and painted them onto small wooden altars.

At the centre of the exhibition is a moving model train with pine needles in the cargo, traveling through a miniature wonderland of stones made of chicken wire, plaster and paint. The constant motion of the train on the oval rail symbolises the flow of life. Alongside, there is a golden made-to-measure hotel luggage trolley, a stand-in for the fast paced lifestyle and a reminder of how people constantly check-in and out of our lives. Silkscreen printed aluminioum sheets and lottery ball sit against the walls, standing in as flashbacks of old memories that I captured for years.

Installation view @Barbican Art Trust Group

It is a new set of works made in response to a 6-week residency at The Barbican Arts Group Trust.

During the residency, I explored the absurdity of life and the fragility of human beings through looking at certain belief systems seen as universal across all cultures of mankind. Setting aside religion, there are numerous ordinary objects designated to offer us false hopes and reassurances. The blind belief we tend to have in objects such as Bonsais, mineral stones, horseshoes, four-leaf clovers, or rabbit feet have created expectancy in our subconscious mind and keep us weathering through the unknown future. Worshiping such deified objects evokes profound emotional responses and further changes our neural functioning. I chose certain symbols that represent just such responses and painted them onto small wooden altars.

At the centre of the exhibition is a moving model train with pine needles in the cargo, traveling through a miniature wonderland of stones made of chicken wire, plaster and paint. The constant motion of the train on the oval rail symbolises the flow of life. Alongside, there is a golden made-to-measure hotel luggage trolley, a stand-in for the fast paced lifestyle and a reminder of how people constantly check-in and out of our lives. Silkscreen printed aluminioum sheets and lottery ball sit against the walls, standing in as flashbacks of old memories that I captured for years.

Humorist R. E. Shay is credited with the witticism,“ Depend on the rabbit’s foot if you will, but remember it didn’t work for the rabbit.”

Wonderland (2020)

Wonderland (2020) Chicken wire, concrete, horse shoe, mild steel, model train, paint, pine needles, plaster, scratch card

133x 80 x 40cm

Moon Stone (2020)

Moon Stone (2020) Chain, chicken wire, hook, paint, plaster, plywood

33 x 22.5 x 37 cm

Han-Kengai (2020)

Han-Kengai (2020) Clay, hinge, paint, plaster, plywood

33 x 22.5 x 37 cm

Maneki-neko (2020)

Hinge, paint, plaster, plywood

33 x 22.5 x 37 cm

Four Legs Good, Two Legs Bad (2020)

Plywood, print, plaster, bronze, foam, plexiglas, mesh metal, steel,

130 x 28 x 50 cm

![]()

It represents a flash of memories of my family motoring on highways towards a massive supermarket in a suburb. Looking out from the window, there are sometimes trucks filled with living pigs passing by. They are all crammed in the boot; I can only picuture their looks from the ears, noses and tails.

This work consists of 12 whimsical pig trotters, made of plaster and pigments, displayed on a wooden shelf as the rear of the vehicle, lining up repetitively in a manor of ballerinas feet. Among them, one casted in bronze is mythicised into divine figures. The absence of other body parts indicates that those are merely the leftovers in their capitalist world, and the contect depics how the rapid political and economic changes have implacted our perceptions on things. The light-on number plate “Pig 1688” illustrates a popular obsession with the supersitiions that the right conbination of numbers can bring you plenty of good lucks and fortune, accomplanied by a piglet grounted sound playing in loop, echoing the space.

![]()

Installation view @PeakLondon

Plywood, print, plaster, bronze, foam, plexiglas, mesh metal, steel,

130 x 28 x 50 cm

It represents a flash of memories of my family motoring on highways towards a massive supermarket in a suburb. Looking out from the window, there are sometimes trucks filled with living pigs passing by. They are all crammed in the boot; I can only picuture their looks from the ears, noses and tails.

This work consists of 12 whimsical pig trotters, made of plaster and pigments, displayed on a wooden shelf as the rear of the vehicle, lining up repetitively in a manor of ballerinas feet. Among them, one casted in bronze is mythicised into divine figures. The absence of other body parts indicates that those are merely the leftovers in their capitalist world, and the contect depics how the rapid political and economic changes have implacted our perceptions on things. The light-on number plate “Pig 1688” illustrates a popular obsession with the supersitiions that the right conbination of numbers can bring you plenty of good lucks and fortune, accomplanied by a piglet grounted sound playing in loop, echoing the space.

Installation view @PeakLondon

Installation view of Prawns & Pigs @4Cose

Everything about Prawns (2019)

Bait, bronze, cigarette end, clay, gelatine silver print, liner, paint, perspex, pine wood, plaster, plywood, mesh metal, mild steel, sound (00:01:02), video (00:06:39), wax

Dimensions variable

Bait, bronze, cigarette end, clay, gelatine silver print, liner, paint, perspex, pine wood, plaster, plywood, mesh metal, mild steel, sound (00:01:02), video (00:06:39), wax

Dimensions variable

The installation consists of several sculptures, two photographs,

one video and sound, reproducing a leisure activity - indoor prawn fishing. This usually takes place in suburban industrial sites, as a hub and community centre for working class. My aim is to discuss how this social activity develops a broader approach towards bodily labour, culture and political economy.

The pond is made into an octagonal shape as a symbol of good fortune, with a bait of dried prawn situated in the middle, dissolving through time. There are piles of crates with hundreds of clay prawns aside waiting to be dropped into the pond for the next round of momentary pleasure.

![]() Pay for Your Pleasure (2019)

Pay for Your Pleasure (2019)

Bait, foam, found object, key, locker, mild steel, plaster, print, plywood, vinyl

53 x 35 x 50 cm

It discusses the current production of prawns, which is responsible for environmental degradation in the future, such as the destruction of mangroves, wetland, coral reefs, destruction of marine and coastal biodiversity and mass drowning of sea animals and other species. It has also been linked to the entire ecosystem with the ever-growing world population and rising of consumption.

It is an interactive work which audiences are encouraged to move a crate filled with clay prawns on a mobile wooden dolly. During the process, fragments of fragile prawns will inevitably fall to the ground; the floor is spread out with a compressed geographical pattern of destroyed environmental view.

The pond is made into an octagonal shape as a symbol of good fortune, with a bait of dried prawn situated in the middle, dissolving through time. There are piles of crates with hundreds of clay prawns aside waiting to be dropped into the pond for the next round of momentary pleasure.

Pay for Your Pleasure (2019)

Pay for Your Pleasure (2019)Bait, foam, found object, key, locker, mild steel, plaster, print, plywood, vinyl

53 x 35 x 50 cm

It discusses the current production of prawns, which is responsible for environmental degradation in the future, such as the destruction of mangroves, wetland, coral reefs, destruction of marine and coastal biodiversity and mass drowning of sea animals and other species. It has also been linked to the entire ecosystem with the ever-growing world population and rising of consumption.

It is an interactive work which audiences are encouraged to move a crate filled with clay prawns on a mobile wooden dolly. During the process, fragments of fragile prawns will inevitably fall to the ground; the floor is spread out with a compressed geographical pattern of destroyed environmental view.

Superorganism (2019)

Superorganism (2019)Bait, clay, foam, hook, pigment, plexiglas, plywood, vinyl

25 x 38 x 9 cm

Environmental health has attracted much attention from the public due to challenges associated with climate change and micro plastic pollution. The impact of 'invisible' chemical pollution on wildlife health shares the connection of fleeting or shifting appearances, with an undercurrent of psychedelic experience.

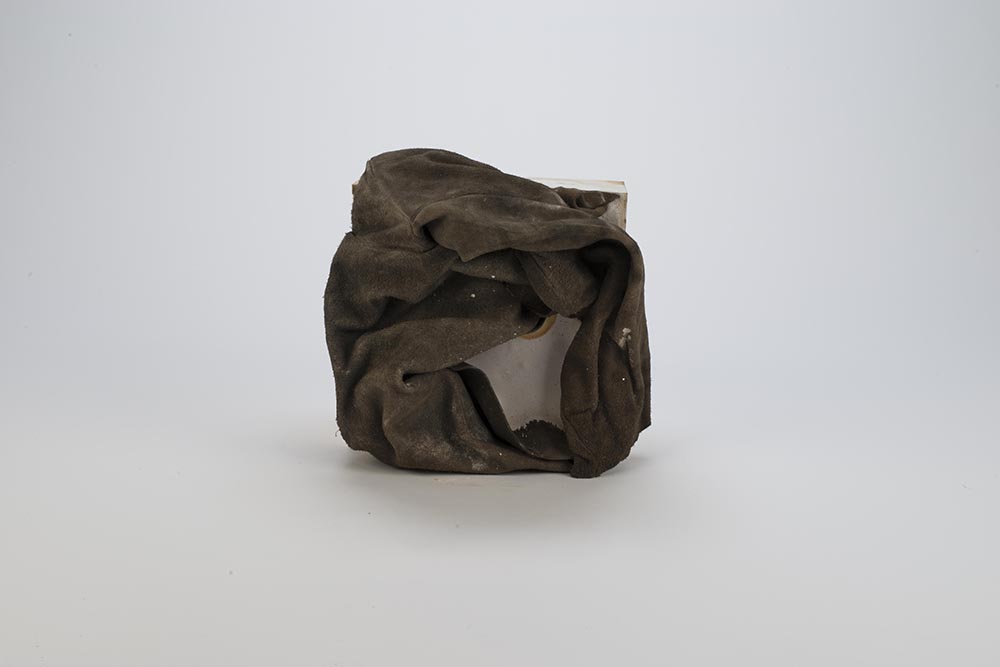

Shattered Memories (2017)

It is a series of works deeply related to my personal life experinece. I believe that clothes have the ability to carry people’s traces, serving as the signposts in the search for the past. In this project weary trousers were combined with plaster and transformed into new sculptures that contain specific time frames and correspodent memories. As time is inscrutable in a way that space is not, this is my attempt to concretise the abstract, the landscape of life into a weighty, monochrome cube/ boards.

![]() Shattered Memories 1 (2017) Plaster, black trousers, 25 x 25 x 25 cm

Shattered Memories 1 (2017) Plaster, black trousers, 25 x 25 x 25 cm

It is a series of works deeply related to my personal life experinece. I believe that clothes have the ability to carry people’s traces, serving as the signposts in the search for the past. In this project weary trousers were combined with plaster and transformed into new sculptures that contain specific time frames and correspodent memories. As time is inscrutable in a way that space is not, this is my attempt to concretise the abstract, the landscape of life into a weighty, monochrome cube/ boards.

Shattered Memories 1 (2017) Plaster, black trousers, 25 x 25 x 25 cm

Shattered Memories 1 (2017) Plaster, black trousers, 25 x 25 x 25 cm

Shattered Memories 2 (2017) Plaster, leather jacket, 25 x 25 x 25 cm

Shattered Memories 3 (2017) Plaster, pigment, Dimensions variable